In the 19th century, an increasing amount of women finally gained

acknowledgment as great artists. Here are ten you should definitely know about.

Rosa Bonheur

Rosa Bonheur, born in 1822, became the richest and most famous woman painter in the 19th century. However, she is rarely mentioned nowadays. Growing up her family was poor, her father was an artist and teacher who taught Rosa and her siblings to paint. Her mother died when she was eleven, leaving a lasting impact on her, and was expelled from school shortly after. Her father let her paint in his studio and she quickly became a great animal painter. She was not scared to go out into the fields and paint close up to the animals while deep in mud. At 19 she was accepted into the Paris Salon Exhibition and won gold a few years later. She had early success as she was commissioned by the French government and had wealthy patrons. An art dealer represented and helped Rosa share reproductions of her work which became quite successful in London. She was the first woman in France to be awarded the Legion of Honor despite her untraditional ways.

In the later half of her life, she lived in a chateau with many different animals including a lioness and tiger. She had two consecutive companionships with women, yet the relationships were never clearly defined. She dressed more masculine and even got approval by the French government to wear pants. Her clothing choices made it easier to paint in the horse and animal markets. Rosa vowed to never marry or have children, dedicating her life to art stating, “As far as males go,” she said, “I only like the bulls I paint.”

After her death, her style of paintings fell out of fashion, only shown in a few exhibitions. Later, she was rediscovered in the mid-20th century; her most famous pieces are now shown in the greatest museums around the world, along with her chateau becoming a museum to honor her art and life.

Mary Cassatt

Mary was born in 1844 in Pennsylvania. She and her many siblings enjoyed a positive childhood benefiting from their parents’ love of traveling and education. At 15 she studied art at college but was unsatisfied with how slow the teaching was along with the condescending nature of her male peers and professors. To her father’s dismay, she dropped out and moved to Paris where she was a new student of prolific French painters. She experienced some success professionally being accepted into the Paris Salon Exhibition, but was still limited due to France’s political turmoil. Women artists were dismissed during the mid-19th century, which Cassatt openly spoke out against. As her career seemingly halted, she was invited to be part of the Impressionists group and exhibit with Edward Degas. The impressionists did not have a manifesto or consistent technique like other art movements of the period, which allowed Mary to continue to experiment. Her family moved to Paris at that time where she enjoyed her mother and sister’s company.

In the later half of her life, she continued to have success in exhibitions and helping other artists share their work. She often influenced American collectors to appreciate impressionism and was an advocate for women’s suffrage and equality. Throughout her life she pushed away the limiting constraints of being a “woman artist” and was respected for her work. She used many mediums in her career but always painted portraits of women and their children with lots of color, conveying a complete story.

Hilma af Klint

Hilma af Klint was quite a mysterious artist, keeping much of her life and work private till after her death. Born in Sweden in 1862, she displayed remarkable talent from a young age. She pursued studies in landscape and portrait painting in both Stockholm and London.

Hilma was deeply intrigued by spiritualism and had a quest for knowledge. She actively participated in group meetings alongside fellow members, engaging in practices like meditation, sermons, and automatic writing. Her studies range from exploring various religions, to delving into the realms of atoms, the natural world, and higher powers. Remarkably, she created over 140 notebooks filled with drawings and symbols over the course of her life.

Hilma was part of ‘De Fem’ (The Five), a collective that consisted of four other women artists who shared her spiritual approach to painting. Notably, she stands as one of the pioneering artists to venture into abstract art, predating the renowned figures like Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky. She described her process as, “The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke”. Her abstract paintings included an array of symbols such as spirals, geometric patterns, diagrams, and flower-like elements.

Klint was aware that the art world was not prepared for her abstract paintings, and she took measures to ensure they remained hidden for twenty years following her death. She bequeathed over 1200 paintings to her nephew who established a foundation in her honor. Only in the last two decades has there been a surge of interest in her art, with the Modern Art Museum in Stockholm dedicating a room to exhibit her work as recently as 2017.

Beatrix Potter

Beatrix, born in 1866 England, was a nature girl at heart. Raised in an upper-class household, she and her brother spent much of their childhood enthralled by the plants and animals outside their lush English countryside home. She was not allowed to attend a school unlike her brother, however her beloved governess ensured Beatrix was well educated. That love for the animals in the lush landscape spurred her most popular children’s series, Peter Rabbit. Her cute but mischievous characters were first brought to life in the form of letters to her friends and the governess’s children. Throughout her life she wrote and illustrated 28 books, selling over 200 million copies today. She was also one of the first authors to license her characters, making games, stuffed animals, and more out of the Peter Rabbit series.

She was not just an author though, she was fascinated by botany and the plants around her, oftentimes drawing very detailed illustrations of fungi. In her studies, she was one of the first people in the world to understand and write about symbiosis. Even though she spent 13 years of her life researching and writing those scientific papers, she did not receive support from her male peers. They wouldn’t even discuss her drawings. Presenting her own work was impossible making her uncle the only person who could share her work in a scientific space. However, without other women like her, in both publishing and science, we would be much further behind in the opportunities and space given to women in these fields.

Later in life, she transitioned into conservation. Beatrix lived in one of the most stunning places in England, up north in the Lake District. She preserved a large area consisting of over 15 farms and cottages, later taken over by the National Trust and are still protected lands today.

Gabriele M ünter

Gabriele was born in 1877 Berlin and always had an interest in drawing growing up. By the time she was twenty-one, both of her parents had died leaving her and her sister a large inheritance. To be with family, the sisters visited their extended family in the southern United States where Gabriele filled many sketchbooks with the surrounding landscapes. Two years go by and Gabriele moves back to Germany, taking classes at any art school that would accept women. She studied woodcut and sculpture at the Phalanx School, an avant-garde school run by Wassily Kandinsky. The two of them had a personal relationship for over a decade. In the ten years together, Wassily taught her to paint more freely, which Gabriele was grateful for. She exhibited her work along with other German expressionists in Wassily’s artist group ‘Der Blaue Reiter’ (The Blue Rider) until the 1930s when tensions rose in Germany. Expressionist paintings were labeled as “degenerate” art by the Nazi party, so during the war, she protected and hid many paintings of artists in her circle. The paintings were never found despite the many house searches by the Nazis. Post-war she continued to paint and exhibit her work, as expressionism had become celebrated. The City of Munich awarded her the Gold Medallion of Honor for hiding away the many precious paintings and keeping them safe from Nazi hands. While Kandinsky overshadows her, she remains to this day one of the most influential women in German expressionism showcasing a unique color palette of yellows, pinks, and blues.

Vanessa Bell

Vanessa Bell, born in 1879 London, was a post-impressionist painter whose legacy has been overlooked for quite some time. She was born into an upper-class family that recognized the significance of educating their many children in writing and the arts. A year after her mother’s passing she pursued painting at the Royal College of Art. Living in the Bloomsbury area alongside her many siblings, fellow artists, and intellectual friends, she played a pivotal role in forming the Bloomsbury Group. Vanessa took the initiative to host meetings and welcome friends into her home, nurturing a creative space for painters within the group. Displeased with the prevailing Victorian painting trends, she began producing increasingly abstract work after attending a Post-Impressionist Exhibition. Vanessa exhibited her work alongside Bloomsbury artists with whom she had intimate relationships with at the time.

Along with painting, she designed textiles and dust jackets for her sister, Virginia Woolf’s books. Vanessa designed all of her sister’s first edition covers, thirty-eight in total. Despite her brother-in-law’s dislike of her covers, she was always supportive of her younger sister and became an influential book designer in the process. Towards the end of her life, she spent most of her time with her children and grandchildren, often painting commissions with them. She was one of the first pioneering women in modernist art to make a significant impact on the scene, and she has since become one of the most renowned painters of the Bloomsbury Group.

Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O'Keeffe was born in 1887 to dairy farmers in Wisconsin. She was the second of seven siblings and knew she wanted to be an artist by the age of ten. In her early adulthood, it was hard to finance her art career, often taking teaching jobs to stay afloat. She was discovered by Alfred Stieglitz after sending her charcoal drawings to a colleague. He was enthralled by her work and held an exhibit of her paintings in one of his galleries in New York. Stieglitz formed an artist circle comprising many early modernists, among whom Georgia is now the most famous. Although she achieved success painting the skylines and structures of New York, her true passion lay in capturing nature, often leading her to escape the city for extended periods.

Georgia visited New Mexico with a friend and was captivated by the desert's beauty. She went through various phases in her paintings including depictions of skulls, desert landscapes, and most notably close-ups of flowers. When she eventually relocated to New Mexico full-time, she had already established herself as a successful and highly renowned artist. However, the scrutiny and pressure took a toll on her, leading to periods of depression and anxiety that kept her isolated. She wrote many letters to her far-away artist friends, including Frida Kahlo, with whom she shared a deep fondness. By the end of her life, she had created over 900 paintings, solidifying her status as the most successful woman artist in the modern era.

Throughout Georgia’s lifetime and in subsequent analyses, many art critics attempted to impose sexual interpretations onto her work, asserting that her floral paintings are connected to the female body. However, she firmly rejected the male-centric perspective on her art, stating, "When people read erotic symbols into my paintings, they're really talking about their own affairs." Like many of the female artists of her era, she had to emphasize that one's gender has no bearing on their identity as an artist, saying, "femaleness is irrelevant" and highlighting that "it has nothing to do with art making or accomplishment."

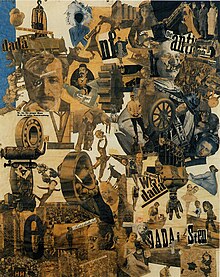

Hannah Hoch

Hannah Hoch, born in 1889 Berlin, was the only woman to be named as part of the Dada movement. When she was 15, she started taking classes in glass and graphic arts to please her father instead of the fine arts she would have preferred. After World War I, she designed craft patterns for a Berlin magazine which opened her world to photomontage. Her partner Raoul Hausmann brought her into the Dada artist circle, a group of artists using photomontage and avant-garde art to illustrate the chaos of post-war Germany and the controlling government. The group had many exhibitions where Hannah Hoch’s work was often the crowd favorite, even though the men in the Dada circle did not respect her as an equal. During this time in Germany, the idea of the “new woman” emerged which included short hair, dressing more masculine, and working to support themselves. Hoch saw right through this romanticized notion as she experienced the disrespect and sexism that men would say behind closed doors even if they celebrated the idea in public.

She split from Raoul after dealing with his often violent outbursts. Shortly after, she lived a private life in a relationship with Mathilda Brugman. Hoch continued to work in mixed media and collage throughout her years, even when her work was named “degenerate art” by the Nazi regime. Her work was always about mass media, government structures, and current events, often in relation to the female experience. The Dada movement, which was a small part of her artistic career is often the only time she is brought up within art history even though she was well-known for over five decades after the movement ended.

Benedetta Cappa Marinetti

Benedetta, born in 1897 in Rome, spent her early years in a warm and loving family alongside four brothers. Her life changed significantly when her brothers, who were acquainted with futurist thinkers, inspired her to pursue a career as a painter. Mentored by Giacomo Balla, he introduced her to the futurist style of abstract and dynamic painting.

Futurism, like several other art movements of its time, emerged amidst political unrest and formulated its own manifesto. However, it’s worth noting that the manifesto faced internal criticism and was disavowed by some of its own members. During this time, Italy lagged behind other leading nations in terms of technology and industry. The futurist writers and authors, while holding divergent views on feminism and fascism, shared a common vision that technology would rescue Italy from its declining trajectory. Benedetta’s unique position was instrumental in preserving futurism’s path, as she was married to the founder of the movement, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.

Her artistic endeavors encompassed a wide array of mediums, ranging from poetry and metal sculptures to novels and monumental paintings. She notably applied her skills to create murals in the futurist style, a medium that has gained prominence in museum exhibitions since her passing. A predominant theme in her work was the extensive use of the color blue, characterized by spherical shapes and repetitive patterns that conveyed the futurist concept of capturing the vitality of life, similar to video frames.

Benedetta’s contribution to art history remained largely overlooked for decades following her death, with much of her work remaining undiscovered, eclipsed by the prominence of her husband. Unfortunately, her own thoughts about her work and the futurist movement were never recorded, and only a few sentences have been attributed to her at all.

Louise Nevelson

Louise was born in 1899 in what is now modern-day Kyiv. Her extended family immigrated to the United States during her childhood, and her parents started a new life in Maine. Her father worked as a lumberjack and pieces of wood were a common sight around the house. As soon as she could, Louise moved to New York City, studying an array of art forms. Making a livelihood with her art proved challenging, leading her to exhibit work as often as possible, and expand her network out of necessity. As she grew older, her body of work expanded, utilizing a wider range of materials, and increasingly featuring all-black compositions. “I fell in love with black; it contained all color. It wasn't a negation of color... Black is the most aristocratic color of all... You can be quiet, and it contains the whole thing.” Her sculptures incorporated materials such as wood, metal, plastic, aluminum, and found objects. By the end of her life, she earned acclaim as a master of sculpture.

Specifically Louise’s approach to art became a major influence on the feminist movement, although that was not her intention. One of her most famous quotes is, “I'm not a feminist. I'm an artist who happens to be a woman.” Her character was defined by intensity and unwavering determination, often drawing disapproval from critics. In an era where movements often focused on reclaiming femininity, she broadened the ideals to celebrate individuality, without limiting anyone to their gender.

You can find more art from these women in our planner available now!

Image Credits: Wikipedia